As Waterstones Children’s Laureate, Cressida Cowell champions the value of reading for the pure joy of it. She talks to Absolutely Education about her own magical childhood and the life-changing power of words on page

Words: Libby Norman

Cressida Cowell MBE needs no introduction to her vast global army of readers, transported into magical universes via her bestselling series’ The Wizards of Once and How to Train Your Dragon. She is also champion of younger readers everywhere as the 11th Waterstones Children’s Laureate – a role given to a distinguished author or illustrator every two years. Cowell has the distinction of being both writer and illustrator. Her 2019 tenure – extended to 2022 due to Covid – is an opportunity for her to continue her good work. She is, quite simply, passionate about getting young people into reading – and her passion is infectious. Her Laureate’s Charter sets out exactly what we need to do, declaring first and foremost that every child has the right to: ‘Read for the joy of it’.

What she believes in is the discoveries – the connections – created by the books children love. “Words are the pathways of thoughts,” she says. “The more interesting and complicated, and the wider the vocabulary of the child, the more interesting the thought paths they can take. So that’s why we want to get them reading because they unconsciously absorb, in the form of joyful stories, so many words, so many connections.”

This joy of reading – and of finding connections – is something that Cowell experienced in her own childhood, split between London and a remote Scottish island in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a childhood that sounds delightfully Famous Five from the outside, but she says J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan is a better match. “The Darlings’ house always felt like our London house, and then Peter Pan comes along and they go to this magical island Neverland. I identified with Peter Pan very much – it’s a touchstone book because it felt very much like my childhood,” she says.

On the island, the family were without television or, indeed, electricity (before they built a house, they camped), so entertainment was self-generated. “In many ways it was a classic 1970s childhood,” says Cowell. “In all 1970s childhoods there was an element of freedom – we were just told to come back when we were hungry.” It sounds idyllic, and what harm could small children possibly come to on their own on an uninhabited island? Actually, in true Famous Five fashion, it had its perils. “Scrambling over rocks, exploring caves, going out on our own in rubber dinghies,” she says. “When I look back, climbing the cliffs and investigating the caves completely unsupervised was incredibly dangerous!” There were more practical and necessary activities when adults were involved. “Catching food and making food was a big deal – this was often cooked on a barbecue or open fire.”

“I remember reading aloud to my little siblings – the feeling when they got so excited or I made them laugh. I think that was the ‘oh wow’ moment”

Cowell was head of entertainment, tasked with keeping the younger cousins and siblings amused – a role she threw herself into. “I put on plays, I was very bossy. I had to be because otherwise they wouldn’t listen to what I said. I made up the scripts, I designed the costumes – there was a lot of imaginative life in which I was in charge,” she says. Again, this sounds delightfully innocent in a very 1970s way, although, as she points out, this style of childhood has a far longer history. “Really I’m talking for all of human history – it’s how it was until now.”

Books featured heavily throughout Cressida Cowell’s childhood. “I was mad about books,” she says. On the island you could only read what could be carried on the boat. But what got left on the island was often revisited. “There were a lot of books left on the island – spotty, damp books that I read and reread,” she adds. When children’s fiction ran out she read what was left. “I was reading Dickens and other adult books way younger than normal.”

As part of her role as ‘Ents Officer’, Cressida Cowell would read aloud, and she can still recall the sense of power this gave her. “When I was about nine or ten I had a book I absolutely loved called The Ogre Downstairs. I remember reading it to my little siblings and cousins,” she says. “And I remember the feeling when they got so excited – ‘read me another chapter, don’t stop there’ – or I made them laugh. I think that was the ‘oh wow’ moment, the beginnings of me wanting to do what I do now.”

Secondhand bookshops and libraries were a source of endless discovery. “Like a lot of children in the 1970s, we went to the library once a week – that’s just what you did. They were like sweetshops, and so well stocked back then.” She remains convinced of the importance of libraries, both as a route to get children reading – and to help them find the authors and the genres that inspire them to carry on. “In order to create a reader, we need to give children opportunities to try things and find what books they love.”

Like her childhood, Cowell’s schooling was split between city and country. She attended St Paul’s, moving on to Marlborough because she wanted art in the mix at A level. St Paul’s had said she might be better off doing Latin. She proved them very wrong, since her Art and History of Art A levels meant that after studying English Literature at Oxford she got into Central Saint Martins (then plain Saint Martins) and then University of Brighton to study illustration. “I use every single part of my education now,” she says.

She is critical of the attitude, still prevalent in some sectors, that creative subjects are lesser subjects. ” I think that’s not very forward thinking,” she says. “To treat arts subjects – art in particular – as if they are on the edge rather than at the beating heart of our economy, as well as part of happy, wise and thoughtful lives, seems strange.”

When it comes to the value of art in engaging young readers, Cressida Cowell has no doubts at all. “We are competing against the best screen ever.” She believes children’s visual literacy now runs so far ahead that illustration has become more important than ever. “They are a way in for highly intelligent children who look at a book and find it a bit baffling. And especially if children have a learning difficulty, books can make them feel stupid – and how can you love something that makes you feel stupid?”

“Children who read for the joy of it are just imbibing words. They are just taking them on without having to have a spelling test or an explanation”

Cressida Cowell has personal insight into learning difficulties. One of her sisters is dyslexic and she has a profound sense of how this can affect children’s sense of themselves. “So often, and I thought this with my sister, children were written off.” While things have improved since the 1970s, it’s no coincidence that dyslexia features in Cowell’s stories. In The Wizards of Once, Wish is dyslexic – it is important that she is the writer of the story.

While Cowell wasn’t dyslexic, she was, she says, “profoundly disorganised” – something that meant she was often in trouble. “I was very well meaning, but I couldn’t do things that other children seemed to find easy. I couldn’t get my homework in on time, I didn’t know what the homework was. I didn’t know where my books were. I was in a constant state of bewilderment!” Again, this chimes with her approach to characters in her stories.

“My heroes don’t fit in in different ways. Wish is dyslexic. With Xar, the other hero of The Wizards of Once, his inability to fit in results in defiance. These are behaviours children develop because they struggle to fit in. Hiccup in How to Train Your Dragon is a child who is bullied. My stories are all fantasy stories, but they deal with problems modern children find very recognisable.”

Both the Wizards of Once and How to Drain Your Dragon draw on Cowell’s most familiar childhood landscapes – not only the Scottish island of secret caves and rugged cliffs just made for dragons, but the Sussex countryside where many happy holidays were spent at her grandparents’ house on the South Downs. Writing for her young fan base, she has described that Sussex landscape as the place where you could almost imagine bumping into a Roman soldier.

She has no doubts about why battles between good and evil continue to be among the most treasured elements of children’s fiction. “They are the most important things that we should all be thinking about and talking about. That’s also what has attracted many adults to children’s literature – we know in our hearts that we’re all still struggling to work out what makes a hero, what is our responsibility to our family, to our loved ones, to our wider tribe and the whole world.” Here, she says, younger readers have a very clear vision: “Children are interested in the truly important things in life”.

Beyond their development as people, Cowell sees reading as the gateway to so much more for children – which is why she takes her role as Children’s Laureate so seriously. “The two key factors in a child’s later economic success, let alone their happiness, their educational success and all the other things, are parental involvement in education and reading for the joy of it. And that’s the really key thing – for the joy of it – not because somebody says so,” she says. “Children who read for the joy of it are just imbibing words. They are just taking them on without having to have a spelling test or an explanation of what that word means.”

Cressida Cowell writes about magical places, but she is as intrigued – both as author and Children’s Laureate – by the magic created when children discover reading for joy. “There are three magical powers that reading brings out in children – intelligence, creativity and empathy. Intelligence is the words. Creativity, often through illustration, is the jumping off point for them to create their own worlds. And the empathy is inside a child’s head – they are that hero with magic powers.”

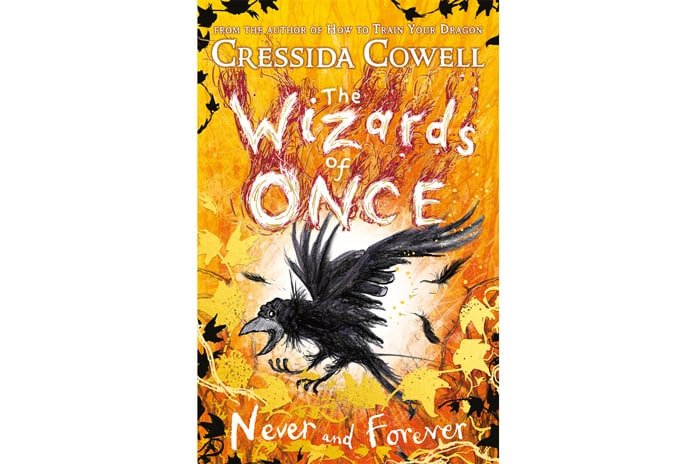

Cressida Cowell’s The Wizards of Once, Never and Forever, is now in paperback (Hodder Children’s Books, £7.99). cressidacowell.co.uk

Further reading: Author Sally Gardner on her own struggle with reading and how we treat dyslexia

You may also like...